Carmen and I are perched on a rock at Ocean Beach on a windy, overcast Saturday in San Francisco. It is November of 1899 and a mass of black unbreathable frocks are taking in the Pacific Ocean, rolling up their trousers and hiking their full skirts.

With no cure for the bubonic plague that recently arrived from Honolulu or wrinkled polyester beachwear you can order from Temu, the crowd is fragile, one flea bite away from the last few pages of a Victorian melodrama. Antibiotics weren’t a thing yet.

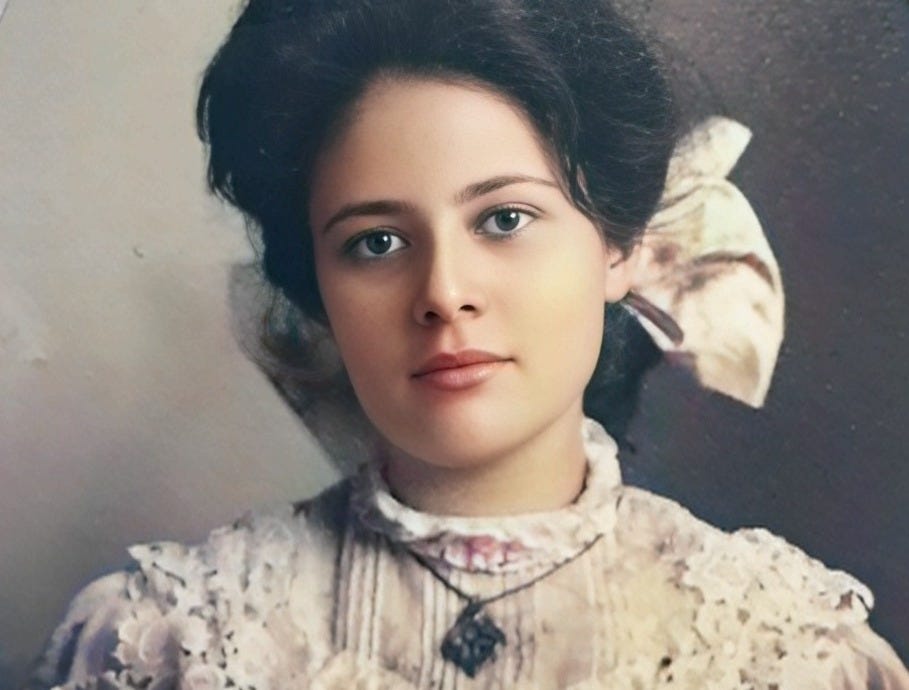

I am trembling. Not for them of course, their as good as dead. The infamous bay area fog is rolling in and the wind is whipping at my face. Carmen is waiting impatiently, rubbing her thumbs against her palms. She has a strong jawline like her son, Ramon Alvino Nemorio (1853-1899) but her full rosy lips and wistful brown eyes soften her. Today you will see who she closely resembles, and I swear dear reader, it didn’t hit me until this past week.

My mother, La Española as you like to call her was born at the beginning of the nineteenth century in 1805 when Spain was still the crown and the idea of independence seemed stupid. Then she goes and dies months before I give birth to Ramon. Then Juan Jóse who you like to call my baby daddy goes and dies a month before he can marry me.

Third great granny? Uh, maybe he didn’t marry you because you were part of a throuple and you just didn’t know it yet?

Well, we will never know Dominique. Juan Jóse is dead and I don’t know what a throuple is.

Fair enough, go on. (She seemed anxious, I decided to go easy on this particular occasion.)

It’s 1853 and Ramon is a newborn and Jose Guadalupe Posada is a baby with a set of pencils. Then I die of yellow fever in 1865 because the French are white glove slapping Benito Juarez, and Ramon is left with Concepción, my half sister and her husband, Francis MacManus. Then in 1894 my son leaves Chihuahua to San Francisco for a better life with his family, and now here we are it’s 1899, it’s November and I am so so very freaked out.

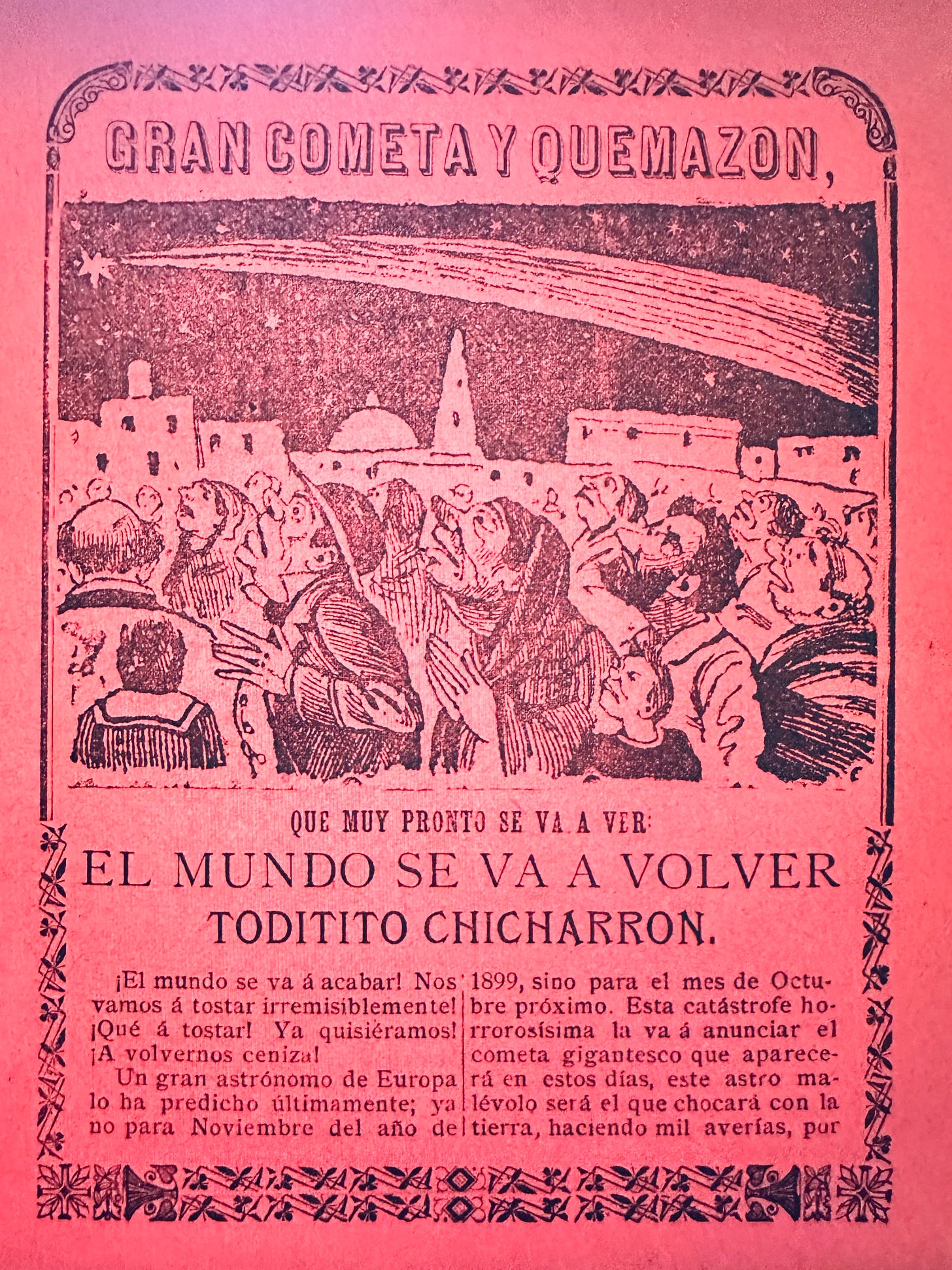

Wait, wut? Why did you just namecheck Jose Guadalupe Posada the printmaker? Mister skulls, political satire and day of the dead shit? Did you have another kid we didn’t know about? Are we finally rich?!?

Jose Guadalupe Posada, the prophet, mocosa, she said.

Prophet?

He predicted my journey.

I’ll bite. How so?

He drew a comet so I could get to Ramon faster.

So you’re saying you’re celestial?

Yes, just like you’re an in demand writer. Go make yourself useful and recount what happened this past Thursday. I can’t bear it. I’m going to go mug that little guy taking nips from his flask behind us.

Whilst Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913) drew a long tailed comet with fearful Mexicans staring upwards, warning that everyone was about to become one big tostada, my second great grand father, Ramon dressed at his home on Ashbury street in the Haight as a lion roared for its breakfast.

The lion roared at 5:45 each morning with Enriqueta grunting in frustration at 5:46. The autumnal warm spell was almost over. Soon, The Chutes by the panhandle would be closing for winter. On this particular day while opening the valve to the radiator, Ramon wondered if the lion would escape if his cage were left open, or would he remain willfully trapped still commanding something to eat? If he did escape, then only Ramon would be left to wake at dawn. His wife slept till it was time to see the girls off to school.

The children loved going to the amusement park. Free falling at The Chutes made them feel brave. Enriqueta hated The Chutes. She couldn’t bear to watch the children ascend the shaky skeletal ladder. She’d argue that they weren’t angels yet like theie babies, Carmen and Juan Jose. The whoosh of the gondola on rollers made Ramon feel lucky, he could enjoy the chaos because then, it would be over.

The radiator sputtered. The steam singed his leg as he pulled his trousers on. He needed to hurry.

He drank coffee in the parlor. A light rain dotted the bay window. Or was it ocean drizzle? When he accepted the position with wholesale company Wellman Peck, the owner said that long ago the Haight was sand dunes and ocean floor like the beach a few miles away. Ramon waited on shipments at the bay countless times but the Pacific ocean always reminded him how far he and his family had drifted from home.

Some coffee spilled on his lapel. The hotel and restaurants would be arriving early for their bulk purchases. Today everyone would need coffee.

At least he’d ring in a new century without chapped skin. Chihuahua had left him brittle.

A crowd of bowler hats waited. The cable car that would take them downtown was running behind. He read his eldest son’s last letter to his mother. Gustavo sounded less dour now that he was in charge of Ramon Carlos. Santa Clara College had been good for his son, he was playing rugby. He assured Enriqueta that his sisters speaking more English than Spanish would help them with other children, and no they did not hate her. Ramon didn’t have that problem, his uncle Francis only spoke to him in English all those years ago when his mother Carmen died. Then Francis died and his boys -like brothers to Ramon, fled Chihuahua.

Carmen, Juan Jose, the names of his parents, and his children - buried side by side in one cemetery. Chihuahua held only ghosts.

The rain smudged his son’s print. He missed his boys.

An ocean of women, he thought, and now I live in one.

When the merchants left with their sacks of coffee and money was placed in the safe, Ramon pushed his chair in. His desk was on the top floor. It overlooked the train tracks. Sometimes he could even see the ship masts from the bay. Tonight it was a dark sky and he could hear the downpour.

Once he was on the ground floor, it would be a long walk on a dirt road to the nearest cable car.

As he waited for the freight elevator, he thought of his eight year old daughter, Maria Luz wearing her brothers old short pants and shirt to ride the Chute a few weeks ago, how she wiggled out of his grip when he tried to take her home before Enriqueta returned. I want to fly one more time through the sky, she insisted.

Named after his godmother—she was a wild little girl but he didn’t care. Her smile was his mother before illness took her, when she wasn’t crying over losing his young siblings to fever, or when two men crushed her spirit, one after the other. Maria Luz was the best of Carmen. People do come back he thought, when you’re not consumed with mourning them.

The freight elevator jerked a few times before it came to a complete stop. Ramon stepped in. He pulled the lever. It began to fall.

He saw his mother Carmen was in bed, fevered and glowing. She reached for him, her palm open, cupped with invisible coins.

They climbed the skeletal ladder. They strapped themselves into the gondola. The lion watched from the sideline. They soared into the breeze and became a memory, slowing to their final resting place.

It was hours before they found him at the bottom of the elevator shaft. He lay in a pool of his own blood. After three days at Mount Zion Hospital, they amputated his leg. It didn’t save him, so the comet flared into the sky.

After pulling Carmen off Pasquale Molinari—who offered to show her his salami collection in exchange for whatever was in his flask—I convinced her to walk with me.

They say you ask for your mother right before you die, I said. Honestly, I didn’t know what to say to Carmen—she was dead, her son was dead. Were condolences even in order?

Pulling the flask she ripped out of Molinari’s hands, she took a swig.

My boy has returned.

On a set of crutches, Ramón was a few feet away. One foot in the sand, the other leg, a bandaged stump. He hobbled toward his mother. Carmen shoved the flask into my chest and ran to him.

They embraced—and vanished where the pacific ocean meets the sky.

I took a swig and went to give Pasquale his flask back. I just love happy endings and salami sandwiches from Molinari’s.

Further Reading: Found SF: A History of the Haight Ashbury, by Janet Mofatt, The Chutes by Bob Burnside The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Jose Guadalupe Posada, Broadsheet relating to the apparition of a comet in Mexico in November 1899, and the words to a song 'La Paloma Azul' The San Francisco Chronicle, November 1899, The San Francisco Call November 1899, courtesy of The California Digital Newspaper Collection, Donate!!!!

Every installment of the Carmen Project inspires me. There are many undiscovered ways to tell a family story. The meaning of someone’s life need not be bound by time and space.