So, you want to move to Spain?

Yes! I said. Get in, third-great Granny! We’re going Europa! We’re going Iberian!

Maria del Carmen Servín (1832–1865) wants to know por qué.

I recounted a meet-and-greet for a Move to Spain masterclass I attended. The majority of aspiring expats were accelerating their move dates to Spain due to the “state of our country.” Many don’t speak Spanish, but they do have the time and money.

Qué cobardes, she said—you especially. Are you dodging literal bullets yet?

No, but we’re slowly being stripped of rights through executive orders, cruel and senseless deportations are happening, and our sitting president’s aspiration to become the Vatican’s next top Pontiff isn’t encouraging.

Once the economy goes, so does any incumbent, she quipped.

The whole country is in an abusive relationship, and more than half are in the “I know he hits me because he really loves me stage”.

Your great-grandfather—my grandson—moved his whole family to Calexico because a hit man was coming after him.

Whatever, Carmen. Tapas are crap in Los Angeles. And we’re not focusing on my hot mess of a great-granddaddy just yet. I want to talk about his brother.

During the Clinton era, I lived in Madrid as a student, and since then, I’ve dreamed of returning to Spain for an extended period. Now that over thirty years have passed, I’m researching how to live there for at least a year once my kids are out of high school. But if I had to flee my native country and claim citizenship somewhere new, I could become a Mexican citizen—though my mother would have to apply first. Both her parents were born in Mexico.

If my set of Spanish great-grandparents had tightened their belts like our president suggests we do, they may have survived the famine of 1904–1906, and my paternal grandmother would have been born in Cañar, Spain, rather than in the United States. That would have a golden ticket to citizenship.

To make matters worse, the dollar is weakening, and fleeing to Europe won’t be like Hemingway in the 1920s, post-WWII Europe, or even the Fuckmaster’s economy. (Did I mention the Spanish boys I used to hang out with called President Clinton that?)

But what if your money had been devalued because it was issued by a mining company, and the whole outfit kept going belly-up? Political unrest was keeping your native country violent, and a world war was about to pull your adopted nation in. You needed to flee—but where?

There’s an unknown territory, the in-between of your motherland, Mexico, and the United States. You ride on your connections: wealthy Mexicans, both conservative and Catholic. You aren’t one of them, but you orbit around their fortunes. Your mother, once a wealthy German criolla in Mexico, is now taking in laundry in San Francisco after your father—whose name you share—died under strange circumstances. The last straw came when your firstborn died in Cananea, Sonora, where you had also begun married life and worked as a banker for that mining company.

The South is rising—but for you, it’s a nutrient-rich desert. The Colorado River flows into the Alamo, but this isn’t Texas; this Alamo is a canal. There is a sea, but it isn’t the Mediterranean brushing up against the shores of Spain’s Andalusia. It’s the Salton Sea—and if you like tilapia, you’re in luck.

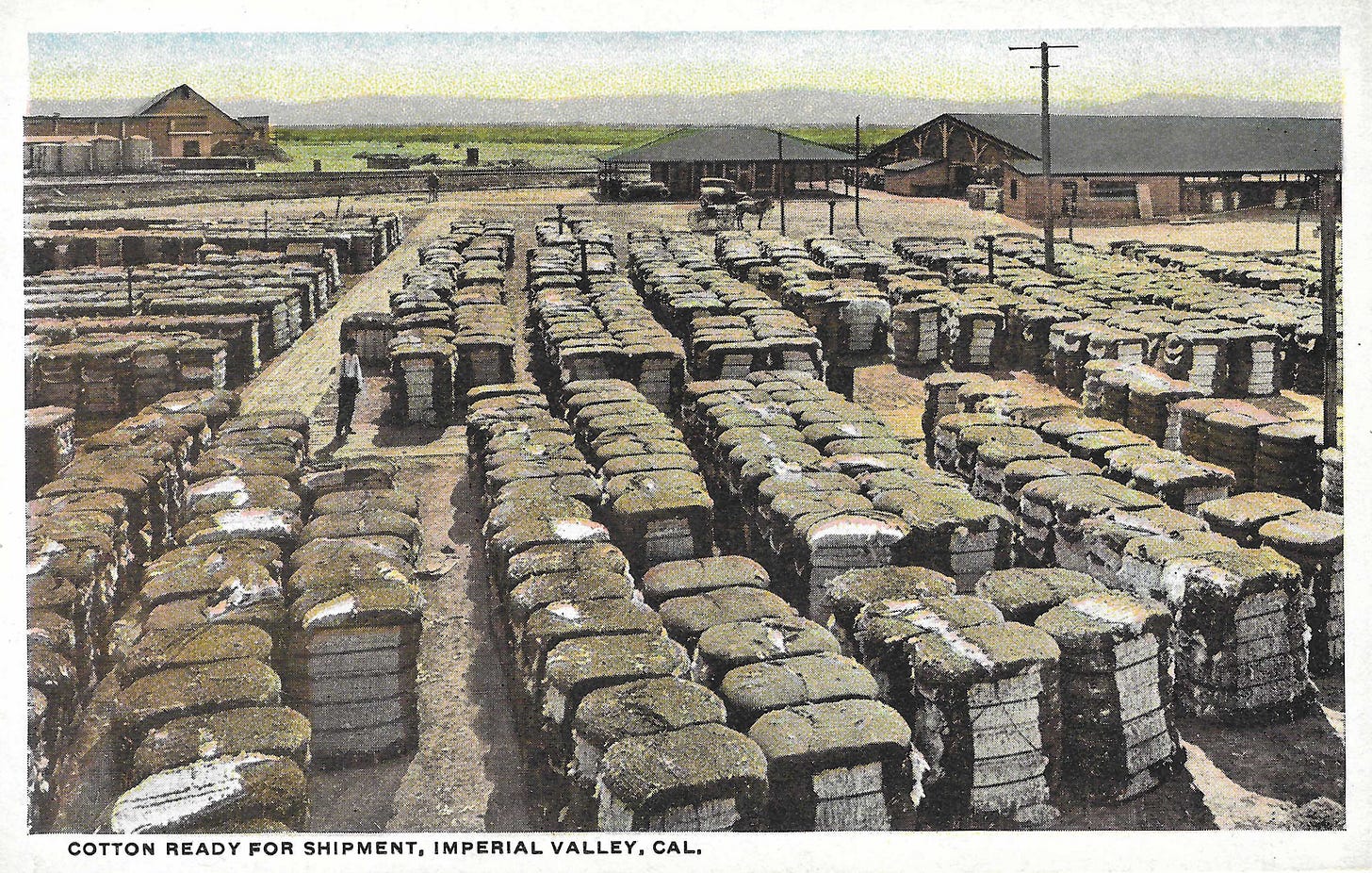

It is July of 1914, and Ramón Armendáriz Jr. (1885–1942), my great-grandfather’s brother, is in search of his fortune. He has arrived in the twin valleys of Imperial and Mexicali—America’s winter garden. Cantaloupe, lettuce, and grapes are being farmed, but cotton has had a particularly successful harvest. Cotton is king in lower California, and Ramón has arrived from San Francisco, leaving his wife and newborn son with his mother and two sisters.

Beyond the lobby of the Calexico Hotel, we find Ramón devouring a smoked chicken thigh. He sits at the dining table of Hiler’s Café—not Hitler’s Café (just kidding, we’re not there yet; this is the WWI era). Hiler’s was known for bringing in fresh seafood daily and importing Utah apples via the railroad that ran through Imperial Junction—now a town called Niland, forty miles away. Chickens and turkeys were plentiful, and Hiler’s was famous for its fifty-cent chicken dinners. But tonight, on this sweltering July evening, it’s free.

July in Calexico is hell. The café’s doors and windows are flung wide open to keep patrons from suffocating in a haze of cigar smoke or the stifling odor of body sweat.

The Farmers and Merchants Association had sent out over 200 invitations to celebrate the valley’s newest industry. They called it a jubilee. Ramón had recently secured a job at the consulate across the nascent border in Mexicali—but that would soon change. I say nascent because the U.S. Border Patrol, as we know it, hadn’t been established yet, and ICE was still just something you desperately wanted in the desert.

Like most early twentieth-century U.S. irrigation projects, the Imperial Valley’s genesis came from federal funding, with prospectors and financiers chasing a big payday. Manifest Destiny and taming the desert—this is what got that wave of men hot and bothered. Just ask Barbara Worth.

Carmen and I decided to invite ourselves to this jubilee of men in Calexico. Most of them were white, but lucky for Ramón, he had been educated in U.S. schools starting at the age of nine. He was fluent in both English and Spanish.

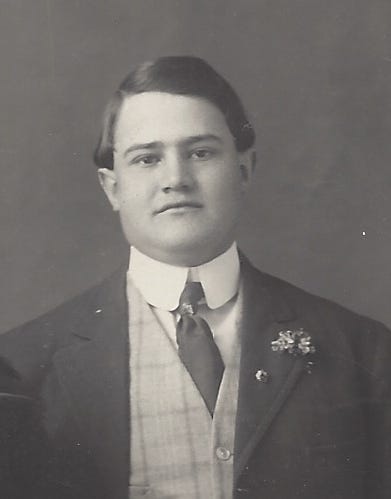

As we pulled in our chairs, I commented to Carmen that Ramón resembled his mother, Enriqueta Ida Moye de Armendáriz (1864–1941).

He’s definitely gained some weight since his wedding, I added.

Carmen grabbed a drumstick her grandson hadn’t inhaled. She shook her head at me in disgust.

Must you body-shame people? Portly was a sign of wealth in those days.

I pelted a chicken bone at her. Must you always be food-aggressive? You remind me of my basset hound.

She took a swig of Ramón Jr.’s punch as I puffed on what was left of his cigar. The evening’s speaker, Adolphus M. Shenk, was estimating that Calexico would grow to 15,000 inhabitants within a few years.

I was seven years old when my mom made me call city hall. The nuns at Our Lady of Guadalupe Academy told us to guess how many people lived in Calexico. It was about 14,000, and it was 1981. I don’t have the heart to tell him.

Nah, let him go on, she said. It’s 38 and change now. Progress, right?

Housing developments, really. Calexico is now an extension of Mexicali.

I threw another bone at her.

Look—both your grandsons were chubby.” Darting my eyes at Ramón, I leaned in and whispered, And it doesn’t help that there are no photos of you, so I blame Enriqueta’s German blood. I can totally picture Gustavo and Ramón Jr. wearing lederhosen and smashing pretzels and sausage. But your son, their dad, Román Sr.—well, he’s how I’d picture Moctezuma the warrior… if Moctezuma went full Victorian steampunk. I assume Juan José—or whoever your baby daddy was—was probably mestizo? Your father was, and we know your mother was Spanish.

Carmen began searching the table for aguardiente or tequila—or whatever Mexican women drank to survive Apache raids and cholera in the mid-nineteenth century.

Oh, and why isn’t Ramón getting a job in San Francisco? I could have owned property in the Haight, for God’s sake. That would’ve made my life so much easier when I moved there in 1998. The parties I would have had!

This blowhard won’t shut up, she said. Coming up empty, she settled for a butter roll.

I handed her the cigar. Careful, sunshine—Mr. Shenk will be your grandson’s boss in a few years. Ramón will run his ranches and make a killing off cotton futures.

Carmen blew a smoke ring at me. I meant you. You don’t have to know everything. As for San Francisco… death moves everyone.

The Imperial Valley’s sister, the Mexicali Valley, was the result of the Díaz regime’s friendliness to foreign investment—without the hassle of Mexican peasants. Angelenos like Harry Chandler and Harrison Gray Otis bought acres upon acres of Mexican land to cultivate cotton. The Chinese were brought in for cheap labor.

Because the revolution dragged on in 1914, Mexican financiers were starting over in places like Los Angeles and San Diego. They were looking for new opportunities. The Baja Peninsula, unconstrained by colonial legacy, could be developed with minimal political headaches—headaches that would rob them of money and land.

A group of Sonoran men would invest in banking and cotton in this relatively new territory. Ramón’s relationships with Sonoran financiers such as Luis Martínez and Aurelio and Próspero Sandoval would lead to him running one of the first banks established in Mexicali—not yet the capital city it is today.

Ramón was searching for success, and within a few years, he would become part of this growing community. His transnational profile and bilingualism helped make border towns like Calexico and Mexicali thrive in the early twentieth century. Both countries worked together as the business of cotton growing transcended boundaries, enriching both nations.

I hang out with Carmen, but I can’t tell you what she looks like. I mostly hear her in my head—but when she’s in my presence, I know I’m home.

It reminds me of eighty years to the day—August 1994—when I landed in Madrid, Spain. Looking out the window of the Iberia plane, I saw fields and fields: agricultural squares, in shades of green and brown. The rain in Spain is mainly in the plane crept into my head, then a lyric I made up:

I went across the United States,

Over the Atlantic to another arid land,

Just to feel safe at home.

Further Reading: Ancestry.com: records of border crossings Mexico to U.S, Calexico Chronicle back issues provided by California Digital Newspaper selection. Cotton in the Mexicali Valley and the Limits of State Interventionism (1914-1950) Araceli Almaraz.

A great collection of family photographs. Sometimes we are drawn to places for a number of different reasons, but we don’t always know the reason at the time. The pull of ancestral connections can be strong.

Thanks Paul! It is true, I never knew how much Spain would fee like home. In 1994, I had was estranged from my father and had no idea what autonomous region his mother's family was from. A quarter of a decade later, I now have family in that region and a writers retreat I went and spent time at. I hope to return again and again.